Kalyeena Makortoff Banking correspondent

11 min read

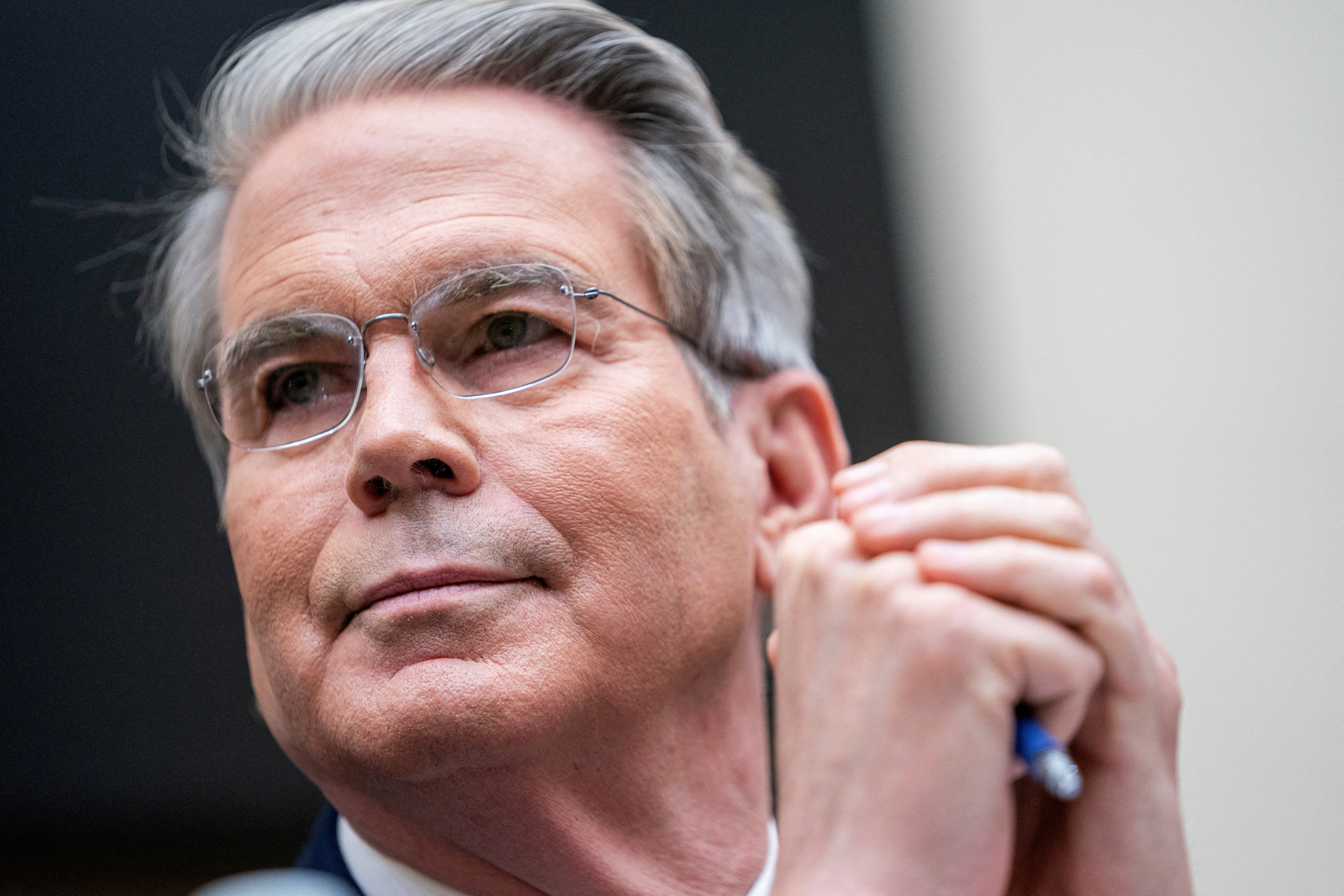

The RBS boss Fred Goodwin in April 2008. His lavish spending and big pension package sparked a public backlash after the rescue.</span><span>Photograph: David Moir/Reuters</span>" height="768" loading="eager" src="data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///ywAAAAAAQABAAACAUwAOw==" width="960">

Hours before the government fired the starting gun on what became a £45bn bailout of Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) in October 2008, Whitehall was in chaos. Dozens of City bankers, drafted in to support the chancellor, Alistair Darling, were camped along the Treasury building’s winding corridors, juggling laptops and mobile phones as they worked to keep the UK’s financial system afloat.

“It looked a little bit like an under-stress NHS hospital,” Charles Randell, the government’s former legal adviser, recalls.

And time was running out. The Labour government, then led by Gordon Brown, had begrudgingly nationalised Northern Rock a year earlier and watched in horror months later as a string of US banks, including Lehman Brothers, went under.

RBS bosses including its chair, Tom McKillop, had been summoned to Downing Street and were told that the government would be taking majority ownership in what was then the world’s largest lender. There was initial disbelief and then acceptance that their charming but ruthless chief executive, Fred “the Shred” Goodwin, would have to go.

Ministers worked fast over the weekend, knowing there would be consequences if they failed to finalise the bailout by Monday morning. Some even feared that customers, queueing to take out their cash, could turn violent. “Who knows whether it would have been necessary to bring the army,” says Randell. “None of that was unimaginable.”

At 7am on Monday 13 October, Brown unveiled an “unprecedented but essential” bailout plan, pumping billions into RBS, as well as into Lloyds, which had recently taken over HBOS, to prevent a financial meltdown. Two subsequent financial injections eventually left the taxpayer with an 84% stake in RBS.

“I recall telling Alistair Darling it could take us 20 years to get the state out of RBS,” says John Kingman, who was then one of the most senior civil servants in the Treasury. He was not far off.

It has taken nearly 17 years for the lender – now known as NatWest Group – to fully return to private hands. The government confirmed on Friday that it had sold the state’s final shares in the lender, albeit at a £10.5bn loss to the taxpayer.

RBS’s near-collapse followed a series of acquisitions under Goodwin that had fuelled its rapid international expansion. He followed a £21bn deal to buy NatWest in 2000 with agreements to buy the British insurer Churchill from Credit Suisse, the German credit card business of Santander, and Ireland’s First Active, as well as a string of small US banks.

The hubris continued, with Goodwin spending £350m to build a lavish campus on the 45-hectare plot of a former psychiatric facility at Gogarburn on the edge of Edinburgh. It included a hairdresser, GP, fitness centre, staff canteen and the CEO’s own plush offices, replete with expensive art and gold carpets.